Introduction

Scenarios are a narrative tool that tells plausible, evidence-based stories about how the future might unfold. They are not predictions but structured narratives that explore multiple, divergent futures based on key drivers of change and uncertainties. They normally follow an environmental scanning exercise where these uncertainties have been uncovered.

The purpose of scenarios is to help us think the unthinkable, to prepare for multiple outcomes, and to challenge assumptions about what the future could or should look like. Even implausible scenarios help us imagine how we might respond and that prepares us better for the more plausible situations.

What it looks like

There are various ways of visually portraying scenarios.

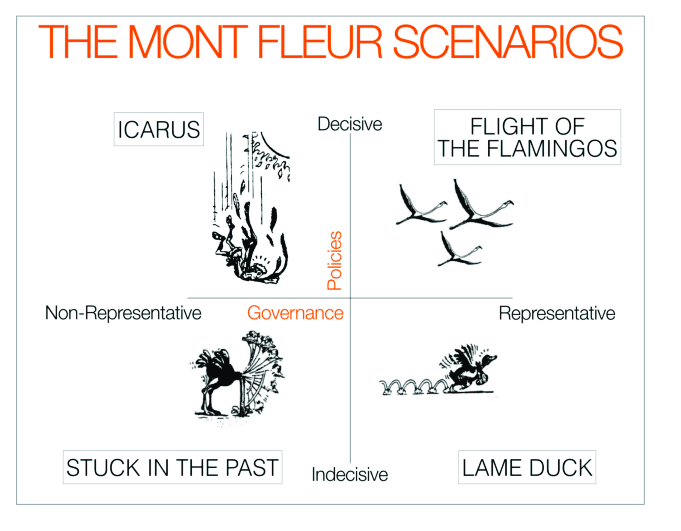

2×2 Matrix of Uncertainties

This is the most common format, using two critical uncertainties as axes to generate four distinct future worlds.

A Scenario Funnel

A diagram that opens from the present into multiple diverging paths, representing the widening range of future possibilities. (Think of the Futures Cone)

Three Futures Typology

This demonstrates the following alternatives:

◦ Possible futures (anything imaginable),

◦ Plausible futures (what could logically happen),

◦ Preferable futures (what we want to happen).

Shell’s Scenario Process Model

This was a repeating set of iterative cycles of scanning, modeling, storytelling, and strategy testing.

Visually, scenario planning is often represented as a branching tree, a set of parallel timelines, or four narrative quadrants, depending on the chosen structure.

How to use it

Scenario work usually involves the following steps:

- Framing the focal question — e.g., “What could the future of [industry/region/organization] look like by 2040?”

- Identifying key drivers and uncertainties from scanning data.

- Selecting the two most critical uncertainties to create a scenario matrix or other structure.

- Developing 3–4 scenario stories. These are short narratives describing how each future might evolve, who the key players are, and what conditions shape them.

- Exploring implications and strategic options under each scenario.

In workshops, participants may develop scenario narratives through group storytelling, creative exercises, or role-playing. It can take the form of written stories, visual posters, videos, or even immersive simulations.

Examples

The Shell Scenarios (1970s–present) remain the classic example. Led by Pierre Wack and Ted Newland, Shell created two primary scenarios around global energy markets: one of continued stability and one of geopolitical disruption. When the 1973 OPEC oil embargo occurred, Shell was the only major oil company prepared with contingency plans, allowing it to adapt faster than competitors.

Another example is the Mont Fleur Scenarios (1992–93), that was developed in South Africa during the transition from apartheid.

Stakeholders from across political divides created four scenarios to explore the country’s possible futures: Ostrich, Lame Duck, Icarus, and Flight of the Flamingos. The process helped foster dialogue and shared understanding during a volatile political period and is now regarded as a landmark in participatory foresight.

When It Is Used

Scenarios are typically used after scanning and issues analysis, once sufficient data and patterns have been identified. They are used:

- To explore uncertainty and challenge linear assumptions.

- To test strategies, ensuring they are robust under multiple possible futures.

- To facilitate conversations among diverse stakeholders about shared challenges and values.

- To support policy and investment decisions, by revealing risks and opportunities not visible through traditional forecasting.

They are most valuable when:

- The future is highly uncertain,

- There are many competing worldviews, or

- Long-term decisions must be made with incomplete information.

Scenarios can also be used this way:

- Corporate Brand Scenarios

Some companies use scenarios to test the longevity of brand values or customer experiences, not just strategy.

Backcasting Scenarios

Instead of exploring forward from the present, practitioners begin with a preferred future and work backward to identify steps needed to achieve it.

- Science Fiction as Scenario

Writers and futurists use speculative fiction (e.g., Black Mirror) as a form of cultural scenario work — exploring moral and social consequences of emerging technologies.

Origin

The scenario method originated in military and strategic planning during and after World War II.

Its intellectual roots can be traced to Herman Kahn, a physicist and strategist at the RAND Corporation in the 1950s and 1960s. Kahn used scenarios to explore potential outcomes of nuclear conflict, later popularizing the technique through his 1967 book The Year 2000 (with Anthony Wiener).

The approach was later adapted for business by Pierre Wack and Napier Collyns at Royal Dutch/Shell in the 1970s, where it became famous for helping Shell anticipate the 1973 oil crisis. The methodology was refined and popularized through Peter Schwartz’s The Art of the Long View (1991), which remains a classic guide to scenario planning in organizations. Over time, scenarios became a core foresight tool adopted by governments, corporations, NGOs, and think tanks around the world.